Also POW’s deserve respect for there War Service.

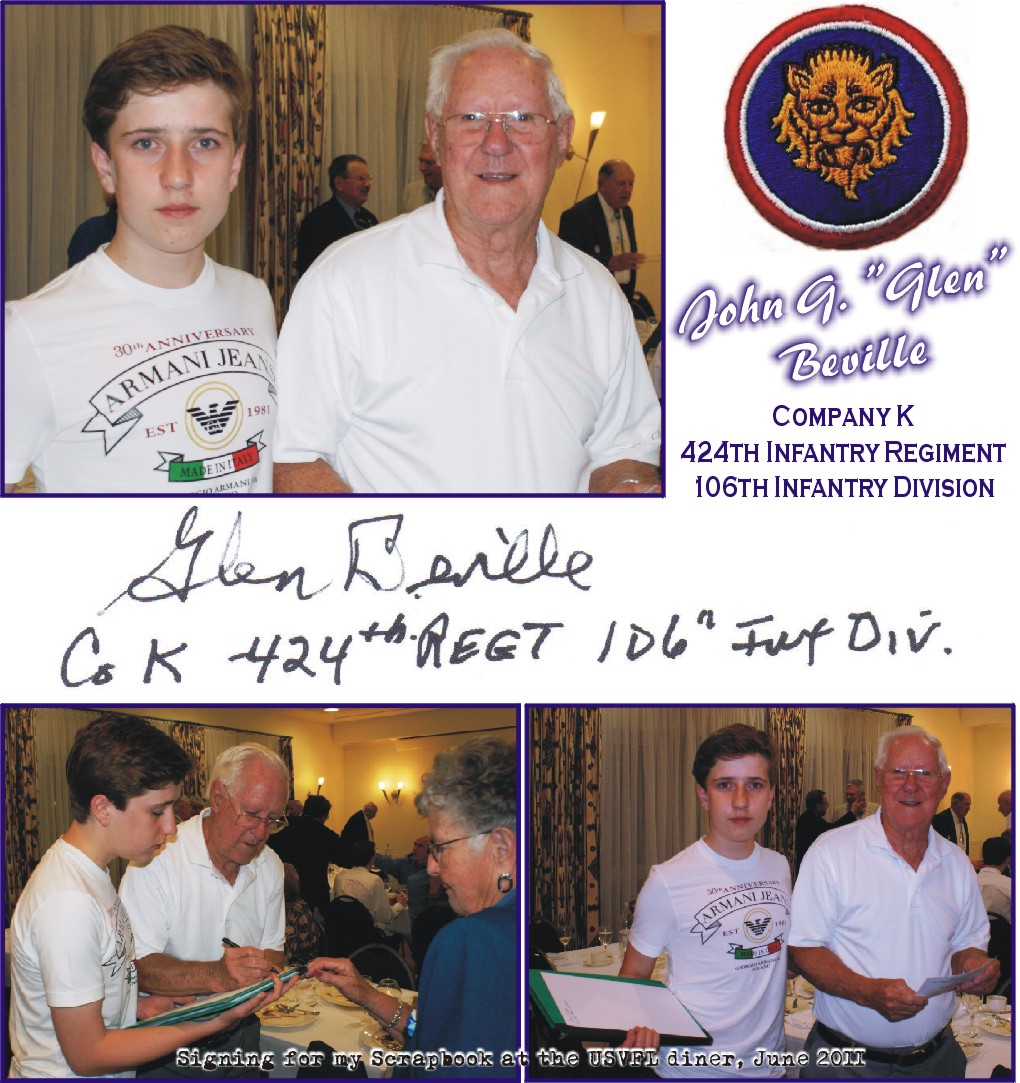

John G. Beville of Fruitland Park, a trim 145-pound corporal who stood 5 feet 9 inches tall, took everything they threw at him as a World War II prisoner of war, and he survived.

From sunup to dark he worked, loading charcoal, digging tank traps, picking up debris after bombings. The grass soup, supplemented by another thin soup made of rutabaga trimmings, was nothing more than slow starvation. They called it grass soup. It was water flavored with lettuce trimmings, cabbage scraps and maybe a potato or two, served once a day. When he was rescued after five months, sick with jaundice and malnutrition, he weighed 82 pounds.

The Germans captured John on December 16, 1944, the first day of the Battle of the Bulge.

The Allies were on Hitler's doorstep, and Germany sent its best troops to the Western front, trying to split its foes and weaken their progress.

The crack German combat forces must have seemed like soldiers from hell to the green recruits of the 106th Infantry.

"We were sent up there as replacements, with no combat experience,'' John said. "They threw their best troops at us and hit us with everything.''

When the shelling began, John was in a bunker five miles south of St. Vith, Belgium. Soon he had fired every round of his M-1. His unit was surrounded and outnumbered. There was no place to go.

With a group of about 200 prisoners, John was marched into Germany and loaded onto a boxcar. There were 60 men to a car, and it was so crowded nobody could lie down.

From there, they went to freight yards, allied bombs falling, on to a POW camp in Luckenwalde, Germany, and then to a work camp south of Berlin.

"We were so far in Germany, there was no way we could escape,'' he said.

Long, hard days with no nutrition wore him down.

"I felt very weak all the time. I didn't want to get up. But if you didn't work fast enough, they'd whack you with a rifle butt.''

Memories kept him going.

"My hometown is Waldo, and we had moved to Wildwood. I used to picture in my mind driving along 301 and 441, knowing my family was waiting for me.''

After liberation, John gradually built up his physical strength, but for years he was haunted by self-doubt, a situation common to many POW’s.

"I felt like I didn't do my duty,'' he said. "I didn't die for my country.''

But when written histories of the war fully explained the circumstances and with his family's support, he gradually acknowledged the position of the 106th was hopeless.

"It was extremely cold, and my feet were frostbitten,'' he said. "We were outnumbered 50 to 1. A Panzer division hit our section. We were just overpowered.''

John was awarded the Bronze Star Medal with two stars, the Combat Infantry Badge, the WWII Victory Medal, the American Campaign Medal, the European-African-Middle Eastern Campaign Medal, the Army of Occupation WWII Medal with Germany Clasp., the Belgium Fourragere and the Honorable Service Lapel Button WWII.

Because he was captured, John never felt that he deserved these awards.

It took more than 50 years for his family and friends to convince him that, despite having been taken prisoner, he had served honorably. He truly deserves this recognition.'

Yes, he does. And as an ex-POW, John's appreciation for democracy runs deep.

"Having lost my freedom, I know what it is to wake up every morning and be able to do what you want to do - and not what somebody else tells you to do,'' he said. "Thank God and your country that you live in freedom.'' conclude John.