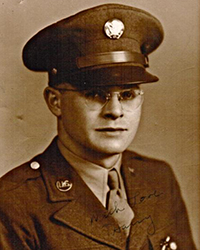

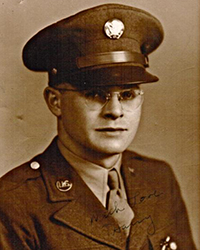

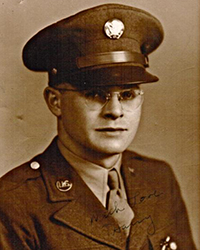

Pfc. Harry J. Kirby Jr.

33339008

C Company, 308th Engineer Battalion, 83rd Infantry Division

October 17, 1917 - December 14, 2005

Pfc. Harry J. Kirby Jr.

33339008

C Company, 308th Engineer Battalion

83rd Infantry Division

Awards and decorations

Biography and Wartime Service

Harry Joseph Kirby was born on October 14, 1917, in Pennsylvania to Leta I. Neal and Harry J Kirby. He lived on South Second Street in Philadelphia for most of his life, graduating in 1935 from the renowned Central High School. He was at home, working with his large collection of model trains on Sunday, December 7, 1941, when he heard the radio news broadcast of the Japanese attack on the U.S. Naval Base at Pearl Harbor. He wanted to enlist immediately, but his eyesight kept him out of the service at first. Still, he continued to return to the recruiters until finally, the fact that he wore glasses didn’t matter any longer.

Harry J. Kirby Jr. enlisted into the Army on October 8, 1942, with entry into Active Service on October 22, 1942 in New Cumberland, Pennsylvania. He trained at Camp Atterbury, Indiana and was assigned to the 83rd Infantry Division.

He married Rita Pitts in September 1943, wearing his uniform with sergeant's stripes and the 83rd patch. John Dillon, another soldier from the 83rd and also a neighborhood friend from 2nd Street, served as best man.

He spoke frequently about his time in the Army and in the war, but, just like many WWII veterans, not about the really bad times, not until much later in life.

June 1944, Shavington Hall, Shropshire, England. We had many cans of gasoline. They loaded up the trucks. We were strictly rationed on gas. That’s when we were getting ready to get into the invasion. We got all of the battalion together. We started down the length of England. That was surprising. All along the main road, there would be line after line after line of weapons, artillery, four or five deep, and on the other side, same thing with tanks, stuff like that. It ran for miles. They had stuff stockpiled like you wouldn’t believe. We got to where we were headed, went into [a building], and were locked in there. We weren’t allowed out, couldn’t send any letters or anything else. We stayed there for a few days. We had no idea what was going on anywhere else. While we were there, the invasion started. That was on the 6th of June. Then we got the word. We drove down to the docks of Portsmouth and they had a ship waiting to load our equipment. On the 9th, we left. Finally, they took us out and we started across the Channel. We were out there chugging across with other ships on both sides. We were about ready to land when a storm came in. The heaviest storm in seventy years. The ship rattled back and forth. Guys were getting seasick and we were running out of food. Then we got the word to move in. When our Liberty ship moved from one place to another [nearing the beach], they would pull up the anchor. When the anchor came up, there were a couple of bodies that floated up with it. There were a lot of bodies there. Every time the tide would go in or out, you’d see more bodies. They were picked up by Graves Registration and taken care of. By the time we landed they weren’t shelling the beaches, the Americans had pushed the Germans back some so we didn’t get shot at much.

Thanksgiving dinner he enjoyed in Steinsel, Luxembourg, at the home of the Pleimling family. A big fan of Christmas celebrations, he told of the Christmas Eve somewhere in Belgium during the Battle of the Bulge, when he and some other soldiers found a box of beautiful Christmas ornaments in a ruined home. Selecting a tree in the forest, they decorated the tree with the ornaments and “tinsel” used as WHAT from American planes. One of the soldiers took a photo of the tree; he was killed in action soon after and the photo was never seen.

December 1944, the 308th Engineer Combat Battalion of the 83rd US Infantry had moved from Steinsel, Luxembourg to Gey, Germany, where they were dug in from December 18 to 25. It was the coldest, snowiest winter Europe had seen in more than thirty years. Hitler’s army was pushing a last ditch counteroffensive against the Allies and the 308th was in the thick of it. It would become the bloodiest battle of the war: the Battle of the Bulge. The Engineer companies supported the Infantry regiments in their attack and support missions.

They worked on extensive road repairs and maintenance, mine sweeping and mine laying, bridge demolition and construction, splinter proof shelter construction and assistance to Artillery battalions in getting to forward positions. Roads in the area were in very bad condition from heavy shelling. Shell fragments covered road surfaces, causing the engineers about fifty tire punctures daily as they hauled gravel in dump trucks to fill shell holes. Working long hours and having support from a Corps Engineer Battalion who worked exclusively on the roads, they kept the most important roads open.

After the War, Harry Kirby Jr. attended The Spring Garden Institute of Technology and Villanova University on the G.I Bill. He was in the business of electrical construction, spending more than 60 years as a member of the International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers. Harry and Rita were married for 21 years until her untimely death in 1964. They had four children: Marianne, Harry III, Joan and James. Harry Jr. died on December 15, 2005, still a member of the 83rd Division Association, former member of the Executive Board and past president of the Philadelphia Chapter. He is burried at the Arlington National Cemetery in Virginia.

I met his daughter Marianne Kirby Rhodes on several Reunions of the 83rd Division Association. For the first time in West Point, New York, 2011.

Thanks to Marianne Kirby Rhodes for the story and the photos about her dad

Gallery

click on the images to enlarge